Receptors for Advanced Glycation End-products (RAGE) are specialized proteins that play a key role in recognizing and interacting with glycation end-products (AGEs). These receptors belong to the family of immunoglobulins and are involved in various cellular processes, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and signaling. RAGE is expressed on the surface of many cell types, including macrophages, endothelial cells, neurons, and smooth muscle cells.

RAGE structure and function

RAGE is a transmembrane protein consisting of three main domains:

- Extracellular domain:

- It contains sites for binding ligands, such as AGEs, as well as other molecules (for example, S100 proteins, HMGB1 and amyloid fibrils).

- This domain is responsible for recognizing and binding AGEs.

- Transmembrane domain:

- Provides binding of the receptor in the cell membrane.

- Intracellular domain:

- Participates in the transmission of signals into the cell after activation of the receptor.

RAGE Ligands

RAGE interacts not only with AGEs, but also with other molecules that can activate the receptor:

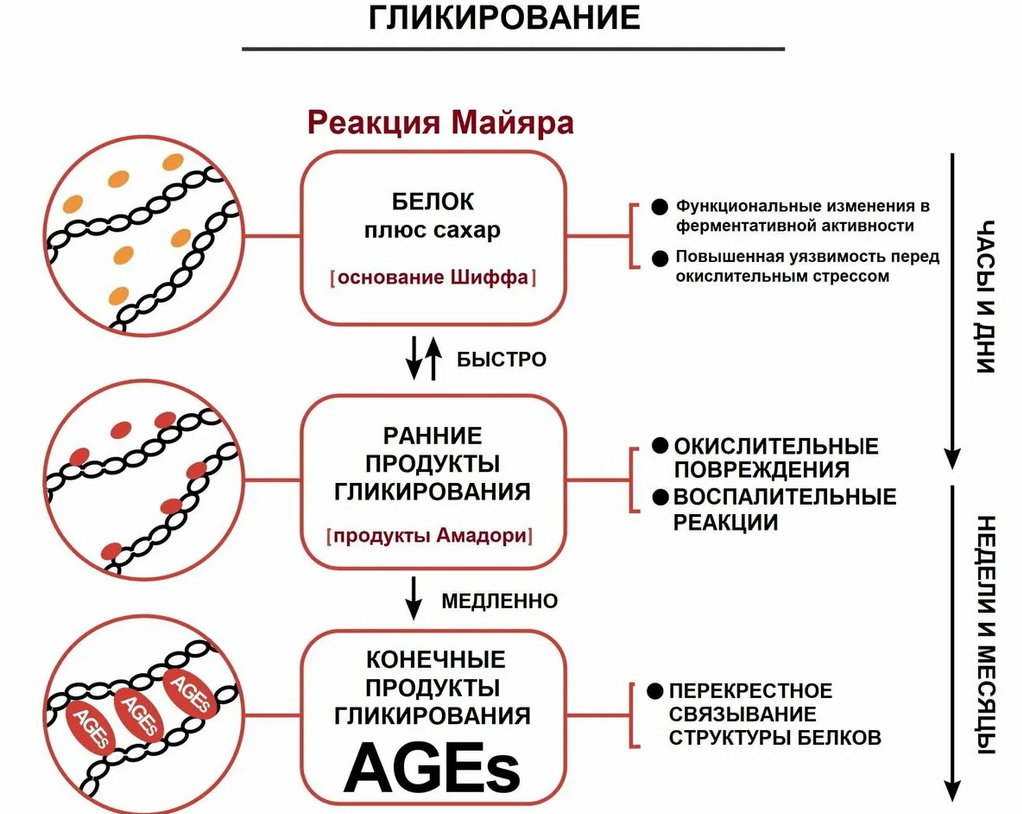

- AGEs: The main ligands that are formed as a result of glycation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.

- S100-proteins: A family of calcium-binding proteins involved in inflammation and regulation of cellular processes.

- HMGB1 (High Mobility Group Box 1): A protein that is released when cells are damaged and is involved in inflammatory responses.

- Amyloid fibrils: Protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Mechanism of action of RAGE

- Ligand binding:

- AGEs or other ligands bind to the extracellular domain of RAGE.

- Activation of signaling pathways:

- After ligand binding, RAGE activates intracellular signaling pathways, including:

- NF-kB (Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells): A key transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes associated with inflammation and immune response.

- MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase): A signaling pathway involved in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

- PI3K/Akt (Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B): A pathway associated with cell survival and metabolism.

- After ligand binding, RAGE activates intracellular signaling pathways, including:

- Inflammatory response:

- RAGE activation leads to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1b, IL-6, TNF-α) and chemokines, which contributes to the development of chronic inflammation.

- Oxidative stress:

- RAGE activates NADPH oxidase, which leads to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increased oxidative stress.

The role of RAGE in diseases

RAGE plays an important role in the pathogenesis of many diseases, especially those associated with chronic inflammation and oxidative stress:

- Diabetes and its complications:

- In diabetes, increased levels of AGEs activate RAGE, which leads to vascular damage (angiopathy), kidney damage (nephropathy), nerve damage (neuropathy), and eye damage (retinopathy).

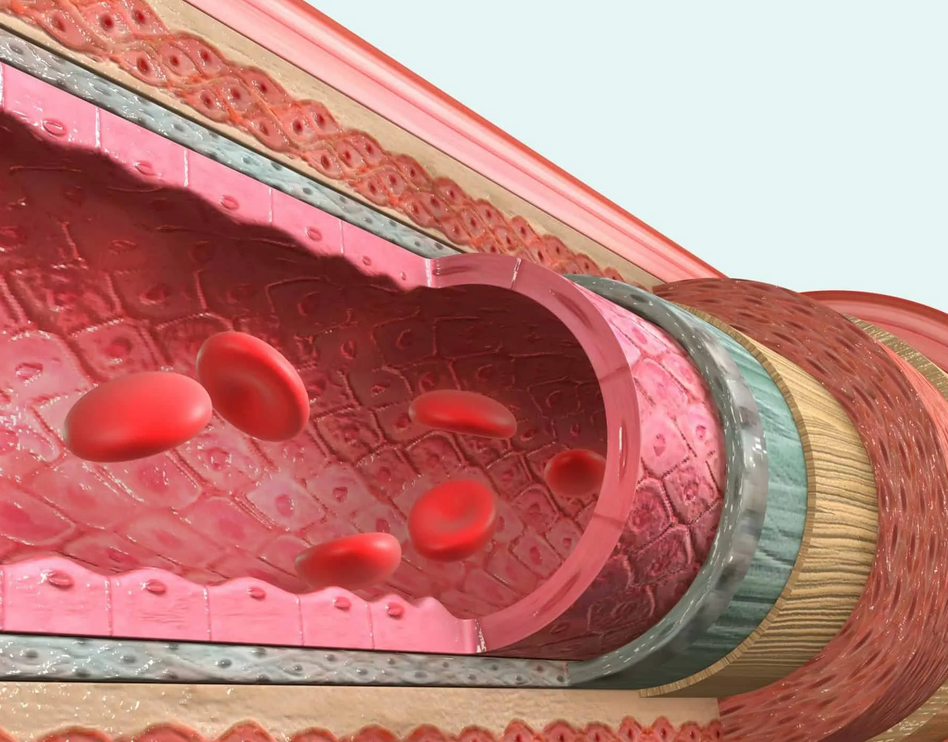

- Atherosclerosis:

- RAGE activation in endothelial cells and macrophages contributes to the development of atherosclerosis by increasing inflammation and oxidative stress.

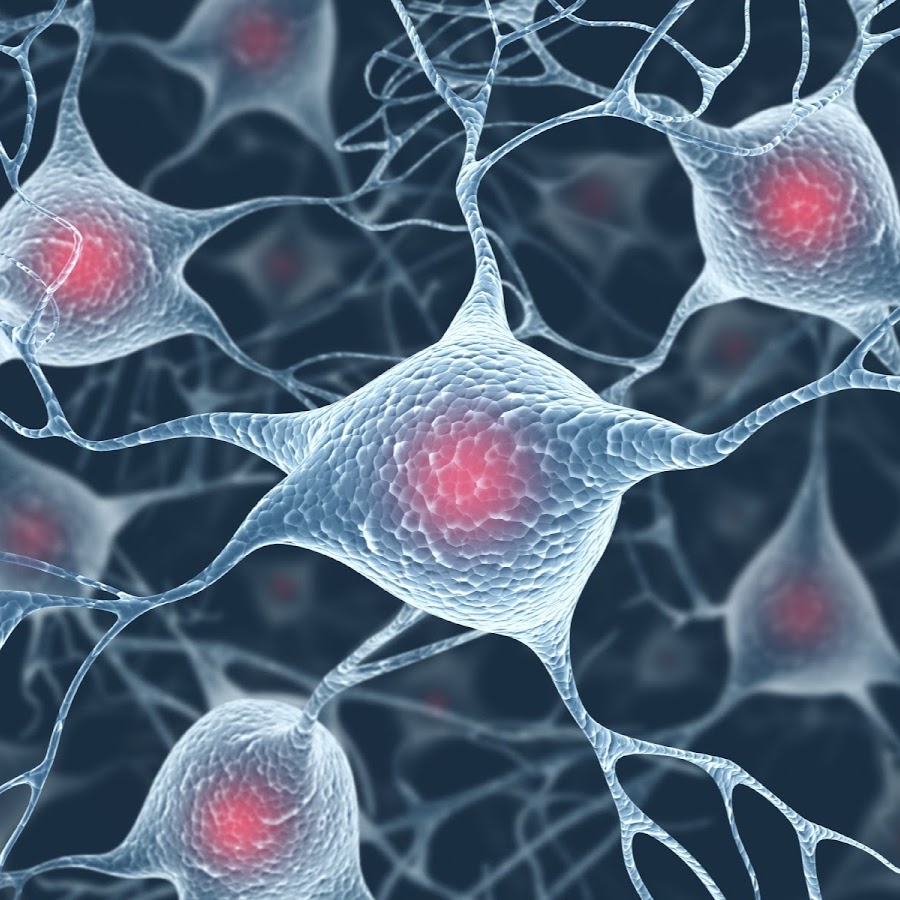

- Neurodegenerative diseases:

- In the brain, RAGE interacts with amyloid fibrils, which contributes to the formation of plaques in Alzheimer’s disease.

- RAGE activation is also associated with neuroinflammation and neuronal death.

- Cancer:

- RAGE can promote tumor growth and metastasis by activating signaling pathways associated with cell survival and migration.

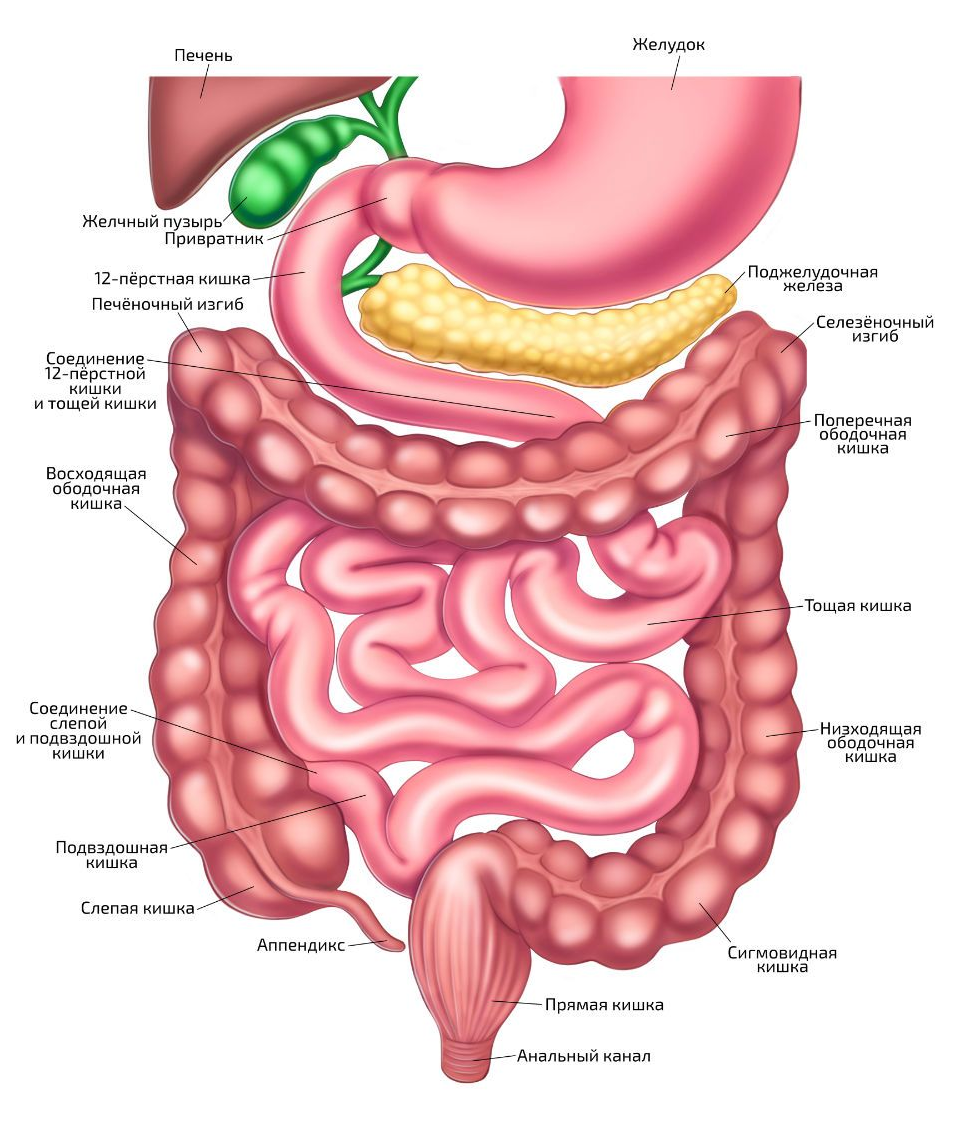

- Chronic inflammatory diseases:

- RAGE is involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and other conditions associated with chronic inflammation.

RAGE inhibition as a therapeutic strategy

Given the role of RAGE in the development of diseases, inhibition of this receptor is considered as a potential therapeutic strategy. Some approaches include:

- RAGE Blockers:

- Drugs that block ligand binding to RAGE are being developed (for example, soluble forms of RAGE that compete for binding to AGEs).

- Antioxidants:

- Reducing oxidative stress can reduce RAGE activation.

- AGEs level control:

- Reducing the levels of AGEs in the body (for example, through diet or glycation-inhibiting medications) can reduce RAGE activation.

Conclusion

RAGE is an important receptor that binds end products of glycation and other ligands, participating in the development of inflammation, oxidative stress and various diseases. Understanding the mechanisms of RAGE action opens up new opportunities for developing therapeutic approaches aimed at treating diabetes, atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathologies.