Contemplation and respect for nature: Food as a form of meditation. It is necessary not to drown out the taste, but to hear it.

Mindfulness in food: Every taste is felt, lived. No receptor overload.

Balance: There is no single dominant taste in the dish, everything is balanced (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami).

Simplicity = respect: If the product is good, why hide it behind sauces? Let him reveal himself.

Minimalism of taste is not a rejection of taste, but an attempt to hear it on a deeper level. . It requires subtlety, habit and attention.

What should be excluded:

Flour. in all kinds and forms.

Sugar in all kinds and forms. Including sugar-containing products, juices and waters.

Hot spices.

Any fast food and food in cafes and restaurants.

Any refined products and semi-finished products.

Any FRENCH fries.

Any alcohol.

Tobacco and drugs.

and here’s why:

Here’s how these foods and substances affect the body’s dopamine system::

1. Flour (any kind)

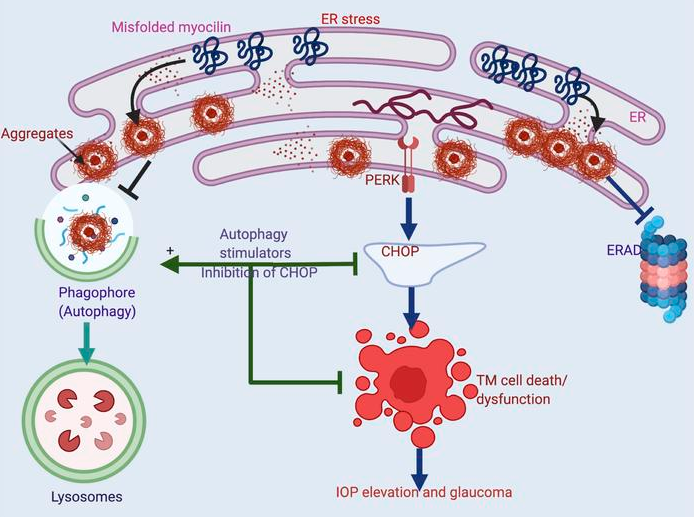

- Effect: A rapid increase in dopamine due to a sharp jump in blood glucose → a subsequent drop below normal.

- Effects: A ‘splash-dip’ cycle is formed, which leads to dependence on flour products to raise your mood.

2. Sugar (including hidden forms)

- Mechanism: Sugar stimulates the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (pleasure center) just like nicotine or cocaine.

- Research: According to brain scans, sugar triggers a dopamine response comparable to drugs.

- Risks: Reduced receptor sensitivity → more sugar is needed to produce the same effect.

3. Hot spices (capsaicin)

- Effect: Capsaicin triggers the release of dopamine through activation of TRPV1 receptors (the ‘euphoric’ effect after a spicy meal).

- Feature: Unlike sugar, it does not cause a pronounced ‘kickback’, but it can form a psychological dependence.

4. Fast food and restaurant food

- Triggers: A combination of fat+salt+sugar → a powerful dopamine response (30% stronger than from home-cooked food).

- Experiments: In an MRI scan, fast food activates the same areas as cocaine.

- Especially dangerous: Monosodium glutamate (increases the ‘dopamine surge’ by 2-3 times).

5. Refined products / semi-finished products

- Problem: Artificially high concentration of ‘taste triggers’ (salt/sugar/fat) → depletion of dopamine receptors.

- Effect: After consuming them, natural food seems ‘fresh’ (it takes time to restore sensitivity).

6. Fried foods (especially fries)

- Key Factor: Acrylamide (formed during frying) → increases dopamine by 40%, but is toxic to neurons.

- Optional: The combination of crispy crust+fat creates a ‘perfect storm’ for the pleasure center.

7. Alcohol

- Action: Blocks GABA receptors → dopamine increases 5-10 times from normal.

- Danger: Each dose of alcohol reduces the baseline dopamine level (more and more are needed to achieve the effect).

8. Tobacco/Drugs

- Nicotine: Increases dopamine by 200% in 10 seconds (the fastest delivery mechanism).

- Heavy drugs: Can increase dopamine by 10-15 times, but completely destroy the natural system of its production.

How to restore dopamine balance?

- Detox 21 days – complete rejection of the above (time to ‘reset’ the receptors).

- Natural Dopamine Stimulants:

- Cold shower

- Physical activity

- Meditation

- Nutritional support:

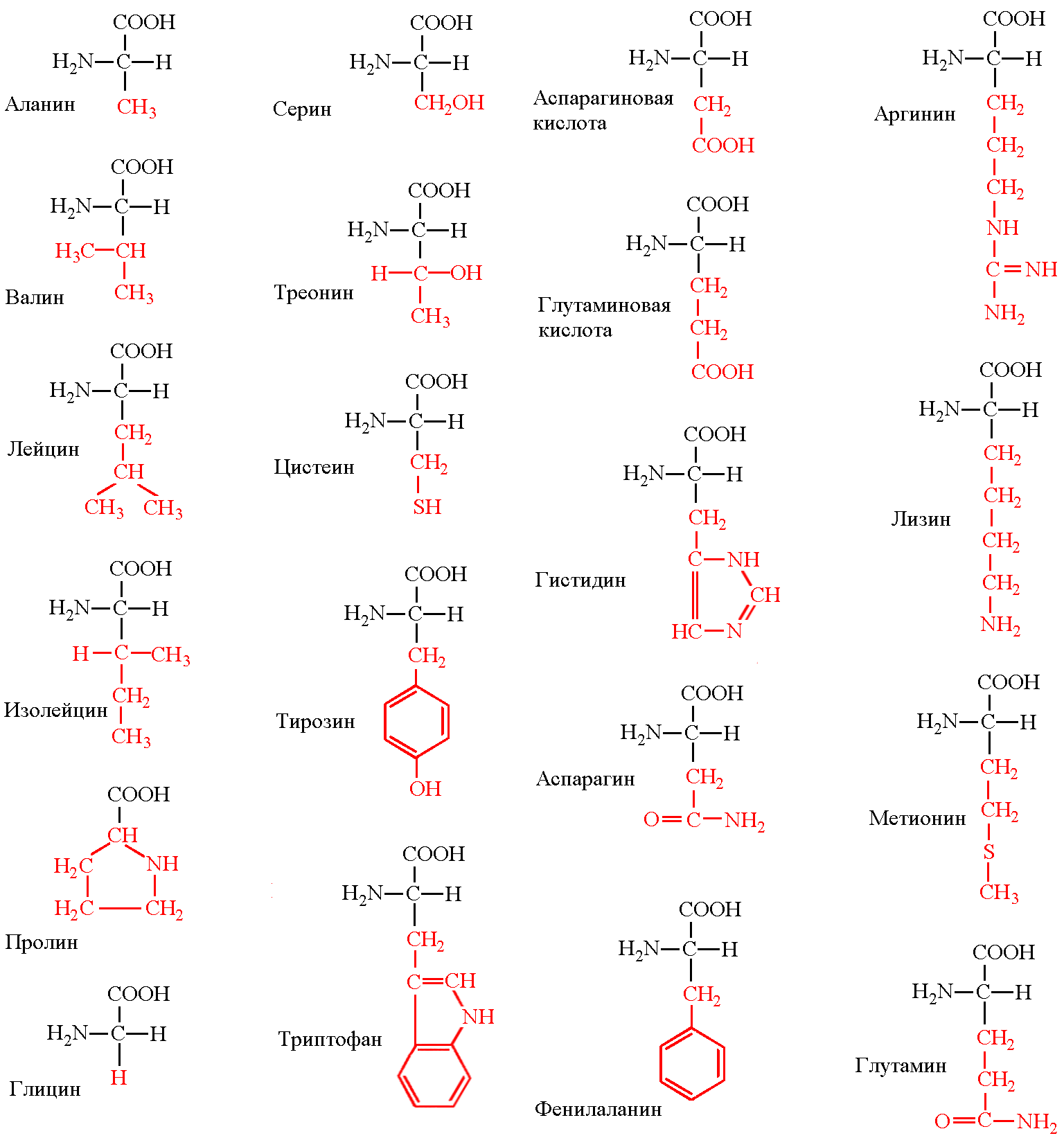

- L-tyrosine (meat, fish, avocado)

- Probiotics (fermented milk products)

- Curcumin (suppresses inflammation in the dopamine pathways)

Important: Full recovery of receptor sensitivity takes 3-12 months, depending on the’ experience ‘ of using the listed products.

And then what happens? and here’s what:

At first, stress and discomfort may occur, but then positive changes will follow.

What will happen in the short term (first days-weeks)?

- Breaking down sugar and fast carbs

Irritability, fatigue, and headaches may appear-this is a reaction to the rejection of sugar and refined carbohydrates (as with a mild ‘detox’ reaction).

Cravings for sweet and flour products will be strong, but after 1-2 weeks they will decrease.

If there was a lot of flour in the diet before, temporary constipation is possible due to a decrease in the amount of fast carbohydrates.

Bloating will decrease (especially if you used to eat a lot of yeast bread or sweet pastries).

As you cut out high-calorie foods, your weight may start to drop (if there was an excess).

What will happen in the long run (a month or more)?

Reduce the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Blood sugar levels will return to normal, and sudden energy spikes and drowsiness after eating will disappear.

- Weight loss (if you are overweight)

The exclusion of flour and sugar dramatically reduces ’empty’ calories, which contributes to weight loss.

- Improvement of skin condition

Less sugar → less inflammation, acne, and premature aging (collagen glycation).

It is possible to reduce swelling (if you used to eat a lot of hidden salt in fast food).

There will be no sudden spikes in glucose → more stable energy levels throughout the day.

- Changing your taste habits

Vegetables and natural products will start to taste better.

Hot spices will not ‘overload’ the receptors, and you will begin to feel the natural tastes of food.

- Improving the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract

Less yeast, sugar, and refined foods → healthier gut microbiota.

- Reducing the risk of inflammation

Fast food and excess sugar provoke chronic inflammation, and avoiding them reduces this effect.

Possible difficulties

- Social issues – it is more difficult to eat out, and you may have questions from others.

- Lack of certain vitamins (if you do not replace flour with healthy carbohydrates) – for example, B vitamins (in whole-grain bread).

- Risk of disruptions – if you can’t find alternatives (for example, fruit instead of sweets, homemade food instead of fast food).

Avoiding these products can significantly affect the search for meaning in life, but the mechanism of this influence is ambiguous. Here’s how it works:

1. The connection between dopamine and existential Search

- When chronically stimulated by ‘fast’ dopamine spikes (sugar, fast food, social media), the brain stops responding to natural sources of joy and meaning.

- Studies show that people with an impaired dopamine system are more likely to experience an existential crisis (Journal of Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2021).

2. What gives a refusal?

- Restoring sensitivity to ‘slow dopamine’:

- The joy of small achievements

- Satisfaction from deep work

- Interest in challenging tasks

- Reduced anxiety (dopamine hyperstimulation increases the ‘I want more’ cycle → frustration)

- Increased neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to readjust and find new patterns of meaning

3. Reverse side (first 2-4 weeks)

- An existential void effect is possible:

- The brain, devoid of the usual ‘crutches’, takes time to rebuild

- The questions ‘What’s the point?’ may become more acute due to the lack of artificial incentives

- This is a normal stage -a sign of the beginning of the transition to a more conscious search

4. How to Increase your Positive Influence

- Substitute practices:

- Keeping a diary (structures thoughts)

- Nature (phytoncides normalize dopamine)

- Social interactions without stimulants (live conversations instead of ‘dopamine’ messages)

- Philosophical work:

- Reading the existentialists (Camus, Frankl) against the background of a purified perception gives other insights

- Practice of ‘ death meditation ‘( representing the extremity of life)

Example from research:

In the MIT experiment (2023) participants after 6 weeks of abstaining from hyperstimulating food:

- 37% more likely to report a ‘sense of meaning’ in everyday activities

- 28% less likely to ask the question ‘ Why all this?’

Conclusion:

A refusal won’t give you a complete answer about the meaning of life, but:

✅ It will create neurobiological conditions for its search

✅ It will remove the ‘noise’ that prevents you from hearing yourself

. It will restore the ability to find meaning in small things

It’s like taking off your glasses with dirty lenses – the world won’t change, but you’ll start to see it more clearly. The main thing is to survive the transition period (usually 21-40 days).